|

| In August 1944, three Allied agents sat in a Gestapo prison in southeastern France, waiting to be executed at dawn. They had been captured, identified, and condemned. There was no time for a rescue, no nearby military unit that could intervene, no way to break into a Gestapo jail. Everyone involved understood that the situation was hopeless.One of the prisoners was Francis Cammaerts, one of Britain’s most effective intelligence agents in occupied France. His capture alone was a devastating blow. The Germans were certain of who he was, and the sentence had already been decided.

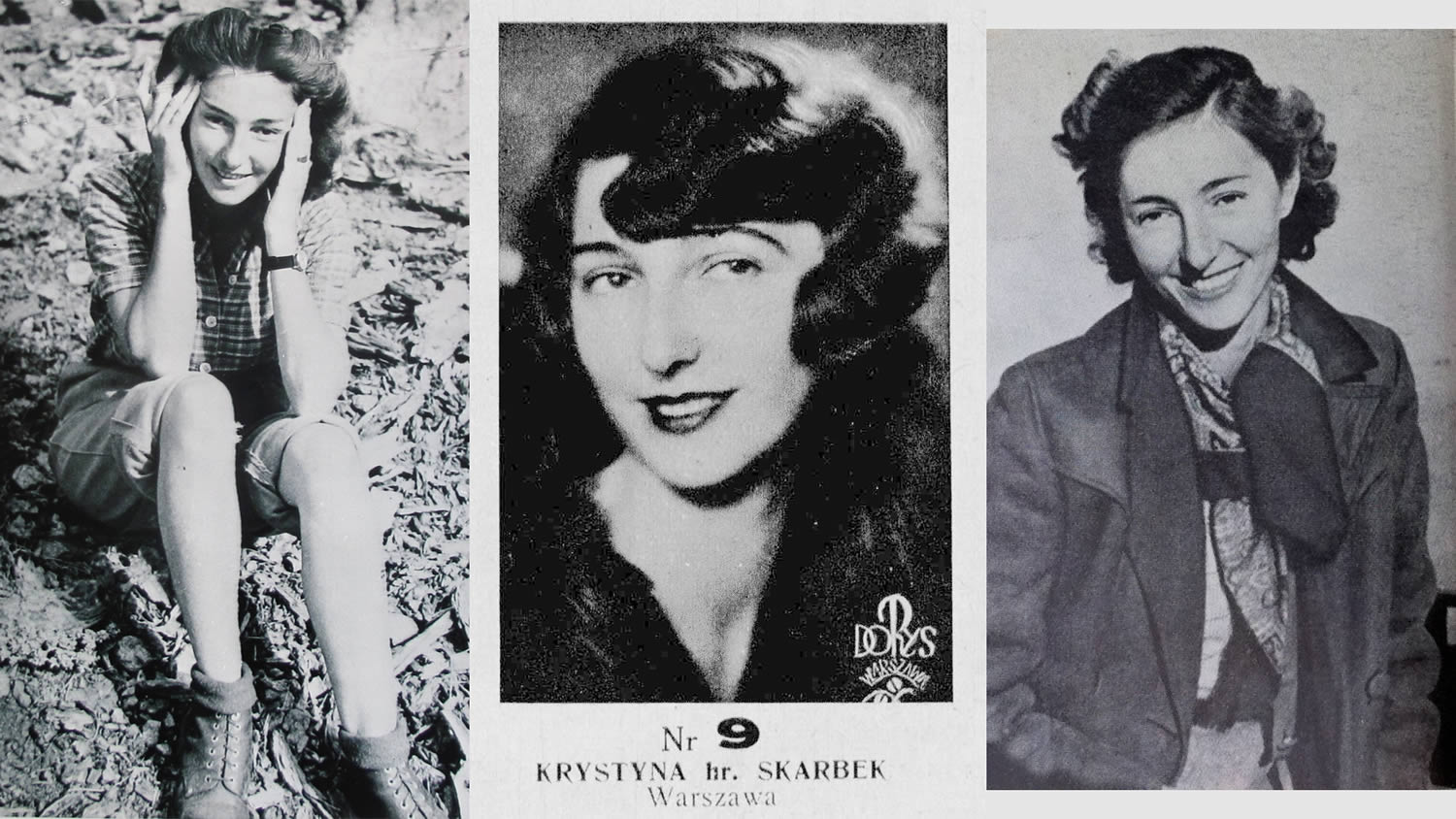

When word of the arrests reached Krystyna Skarbek, she did something no one else would have dared. She didn’t try to plan an escape or call for help. She walked straight into Gestapo headquarters. She asked to see the commanding officer, and when he appeared, she calmly delivered an astonishing story. She claimed she was the niece of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, one of the most famous Allied commanders. She told him the war was effectively over, that Allied forces would reach the town within hours, and that any officer who executed Allied agents at this stage would be tracked down and prosecuted as a war criminal. Then she offered him another possibility. Officers who showed restraint, who released prisoners instead of killing them, might be treated leniently when the Allies arrived. She left him with a simple choice: carry out the executions and guarantee his own punishment, or release the prisoners and possibly save himself. None of it was true. She had no connection to Montgomery, no official authority, and no backup waiting outside. What she had was perfect timing, total nerve, and a clear understanding of fear. The war was turning, the Germans were retreating, and everyone knew it. Along with a substantial bribe, her bluff worked. Whether the officer truly believed her or simply decided not to gamble his future, the result was the same. Just hours before they were due to die, all three prisoners were released. Krystyna Skarbek had talked condemned men out of a Gestapo prison by understanding that, in a collapsing occupation, fear could be more powerful than any weapon. By then, this kind of impossible success was almost routine for her. She had been doing work like this since the beginning of the war. She was born in Poland in 1908 into an aristocratic family and grew up multilingual, athletic, and fiercely independent. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, she happened to be in Britain. She could have stayed there in safety, watching the war from exile. Instead, she walked into British intelligence offices and volunteered. She became one of the first female agents of the Special Operations Executive, the secret organization created to run sabotage and espionage behind enemy lines. Under the cover name Christine Granville, she spent the next five years moving through occupied Europe. She skied across mountain borders carrying microfilm. She smuggled people out of occupied Poland. She organized resistance networks and sabotage missions, often with little support and enormous personal risk. In 1941, she was arrested by the Gestapo in Hungary. Interrogation and execution seemed inevitable. To escape, she bit her own tongue until it bled badly, then pretended to be suffering from advanced tuberculosis. Terrified of contagion, the Gestapo released her rather than risk an outbreak. She walked out of custody and went straight back to intelligence work. After D-Day, she was parachuted into France to coordinate resistance groups and pass intelligence to advancing Allied forces. The Gestapo placed a bounty on her head. Nazi officials across the region wanted her captured. Time and again, she slipped away—until the day she chose not to run at all, and instead walked directly into their headquarters and forced them to release her colleagues. By the end of the war, she had received the George Medal, the Order of the British Empire, and the Croix de guerre. She was one of Britain’s most decorated female agents. She had saved countless lives and carried out missions that genuinely helped shorten the war. And then the war ended, and Britain largely forgot her. When the SOE was dissolved in 1946, its agents were dismissed with minimal support. Krystyna, now effectively stateless because Poland was under Soviet control, was given £100 and told to rebuild her life on her own. The woman who had risked everything for the Allied cause ended up working as a shop assistant, then as a stewardess on passenger ships. She struggled to afford rent in London and lived quietly, far from the world where her courage had once mattered. During this time, she met Ian Fleming, a former naval intelligence officer who would later create James Bond. He was fascinated by her. The strong, capable women in his novels, especially Vesper Lynd in Casino Royale, were influenced by Krystyna. The difference was that in real life, she had never been a side character or a romantic accessory. She had been the decision-maker, the survivor, the one who acted. Her story ended not with recognition, but with tragedy. On June 15, 1952, in the lobby of the Shelbourne Hotel in London where she was living, a merchant seaman named Dennis Muldowney confronted her. He had become obsessed with her and could not accept her rejection. He stabbed her in the chest. She died almost immediately. The woman who had survived the Gestapo, Nazi occupation, and years of war was killed in peacetime by a man who could not accept her independence. Only a small group of former colleagues attended her funeral. There were no official representatives, no military honors, and no public recognition of what she had done. For decades, her name faded from memory. Slowly, historians pieced her story back together. Books were written; documentaries followed. Today, her rescue of Francis Cammaerts is studied as a classic example of psychological warfare, and her career is recognized as proof that creativity, intelligence, and nerve can defeat overwhelming odds. Krystyna Skarbek walked into Gestapo headquarters and talked three men to freedom. She escaped captivity by sheer ingenuity. She spent five years behind enemy lines. She inspired some of fiction’s most famous spy characters, while living a far more dangerous life than any novel could capture. She was born in Poland in 1908 and murdered in London in 1952. Between those dates, she lived a life of extraordinary courage, saved lives, and never asked permission to be brave. Britain forgot her. History did not. |