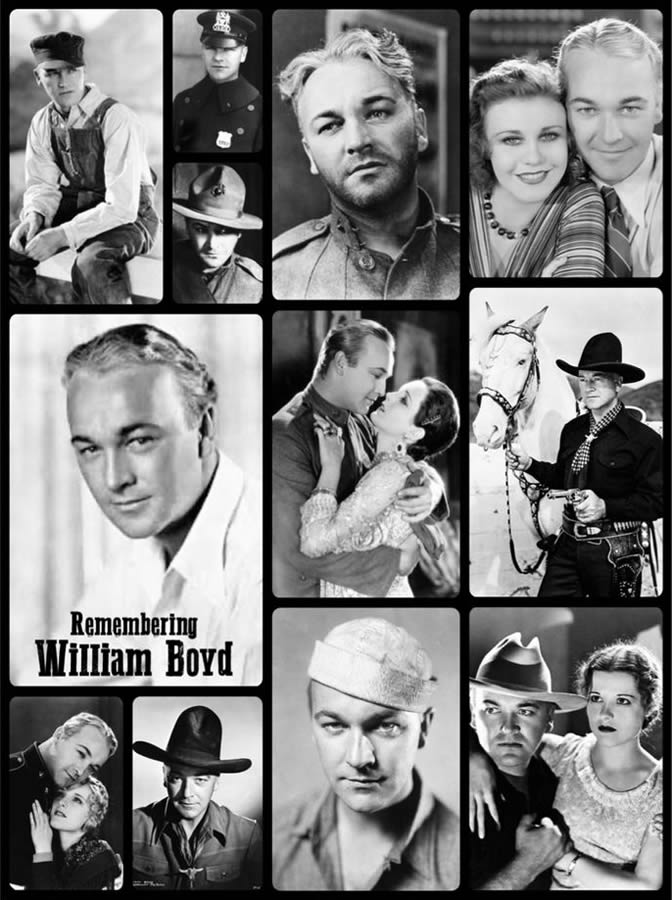

| William Boyd - June 5, 1895 to September 12, 1972 |

|

He had lost everything twice - his fortune, his reputation, his future. And then, when the world thought he was finished, he sold his ranch, bought back the pieces of his broken past, and turned them into gold. This is the story of William Boyd, the man who became television’s first millionaire - because he refused to let failure have the final word.

He was born in 1895, the son of a day laborer in Hendrysburg, Ohio. His family had little, and when both his parents died while he was still a boy, William was forced to grow up before he’d even finished school. At fourteen, he went to work - hauling, surveying, sweating in the Oklahoma oil fields. By his early twenties, his hair was already gray from exhaustion.

But he had one thing that couldn’t be buried under dirt or dust: ambition.

In 1919, he packed everything he owned and rode a train west to Hollywood - a place where men with nothing but hope could become legends overnight. His first job was as an extra in Cecil B. DeMille’s "Why Change Your Wife?" It paid next to nothing, but William dressed the part of a star, polished his shoes, and made sure DeMille saw him.

DeMille did.

By 1926, William Boyd was the romantic lead in "The Volga Boatman", earning over $100,000 a year - a fortune in those days. He was tall, handsome, charming. America’s women adored him. Hollywood worshipped him.

And then, the talkies came - and silenced him.

Like so many silent stars, Boyd’s voice didn’t match the fantasy. Studios stopped calling. His fame slipped away, one whisper at a time.

But the true blow came in 1931.

A newspaper headline screamed: “Actor William Boyd Arrested on Gambling and Morals Charges!” The man in the story wasn’t him - it was another actor, William “Stage” Boyd. The papers had printed the wrong photo. Overnight, his name and photo became poison; the roles vanished; friends turned away.

He was broke again: disgraced for something he hadn’t done.

Years passed. He could have quit. Instead, he waited.

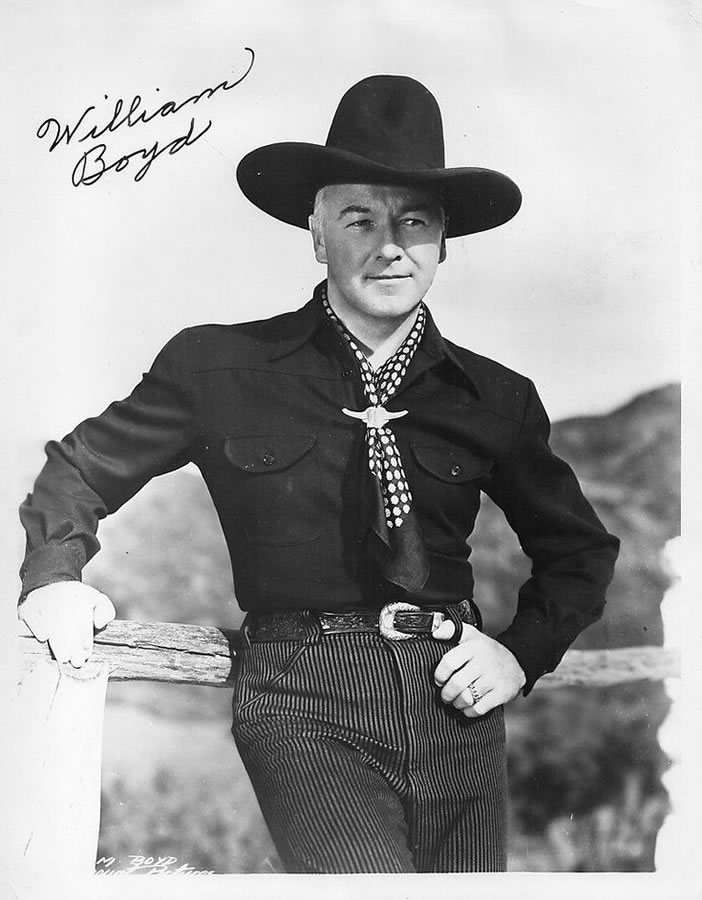

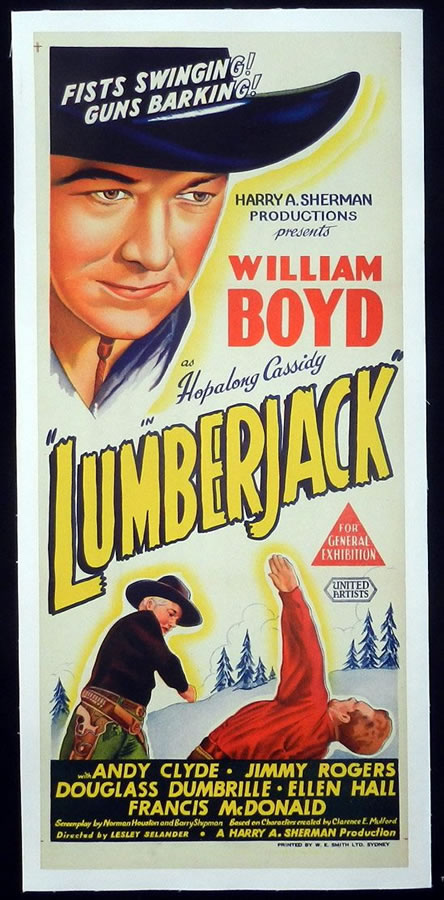

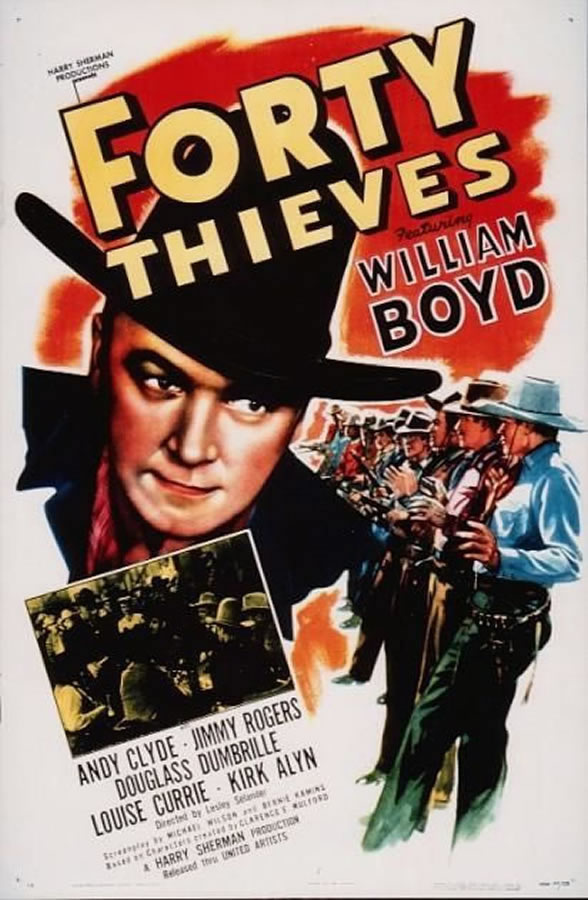

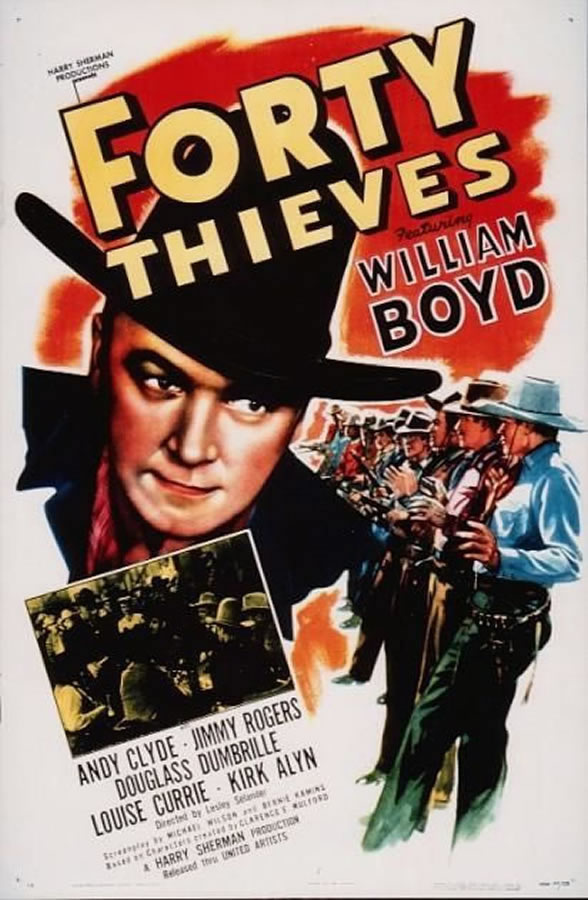

In 1935, a producer offered him a role in a cheap western about a cowboy called Hopalong Cassidy. The pay was modest. The role - a grizzled, one-legged gunslinger - wasn’t glamorous. But William Boyd took it - and he changed it.

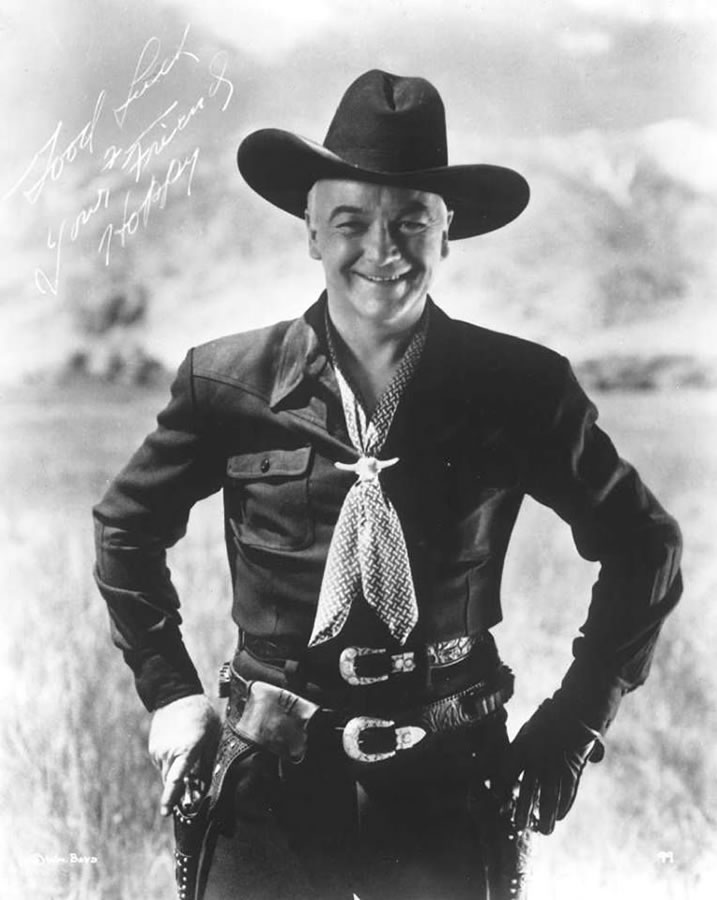

The original Hopalong was a drinker, a fighter, a rough-edged outlaw. Boyd stripped away the vices. He made him honest, kind, gentle: a cowboy parents would trust and children could adore. He gave America its first truly wholesome Western hero.

Between 1935 and 1948, Boyd made 66 Hopalong Cassidy films. They were low-budget, but they made money - steady money. For a while, he lived comfortably again.

Then came the gamble that made him immortal.

By 1948, television was just a flicker - experimental, uncertain, dismissed by every major studio as a novelty. Old westerns were worthless. But Boyd had vision. He believed those films could live again - not in theaters, but in people’s living rooms.

He sold his ranch and poured every dollar - $350,000 - into buying the rights to Hopalong Cassidy.

Friends called him insane. “No one will watch old cowboy movies,” they said.

But Boyd smiled. He’d heard that before.

Within months of licensing his films to NBC, Hopalong Cassidy became the most-watched show in America. Children begged their parents for cowboy hats, lunchboxes, and toy six-shooters. Boyd’s image was everywhere - on cereal boxes, comics, records, and radio shows.

By 1950, 50 million Americans were watching “Hoppy” every week.

He didn’t just star in a show. He created an empire.

He understood merchandising long before Disney, long before George Lucas. Every product that bore Hopalong’s name sent royalties pouring into his pocket. By the mid-1950s, William Boyd was earning more than Lucille Ball, Milton Berle, or any other television star. Over his lifetime, he made more than $70 million - today’s equivalent of over $700 million.

And he did it not by exploiting fame, but by reclaiming dignity.

He’d been wronged by the press, forgotten by Hollywood, and stripped of everything - but he refused to grow bitter. Instead, he became a symbol of decency. Hopalong Cassidy didn’t curse, cheat, or lie - and neither did William Boyd. He visited children’s hospitals, refused to endorse tobacco or alcohol, and made sure his character stayed pure, no matter how much money was on the table.

He’d built himself into the kind of hero he wished he’d had as a boy.

When he died in 1972, television had moved on. Westerns were fading. The world no longer talked about Hopalong Cassidy - but his fingerprints are still everywhere. Every Star Wars toy, every Marvel T-shirt, every empire built on owning your own image: they all trace back to the cowboy who sold his ranch to buy his old movies.

William Boyd didn’t just invent a hero: he invented a business model, and he proved that even when the world confuses you with the villain, you can still come back as the good guy.

He lost everything twice.

He bet on himself both times, and the second time, he made history. |